“Dinosaurs have become boring. They’re a cliché. They’re overexposed” – Stephen Jay Gould

“Dinosaurs have become boring. They’re a cliché. They’re overexposed” – Stephen Jay Gould

Dinosaurs have always been inextricably linked to popular culture. Despite going extinct 65 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous period they pervade our society. Dinosaur exhibits are the main attractions of natural history museums and outside of this setting, they can be found in films, documentaries, books, toy shops etc. A new discovery of one of these animals frequently adorns our newspapers. Even the word dinosaur has entered our everyday language as a metaphor to describe something as hopelessly outdated. Because of this pervasiveness there seems to be an implicit assumption among science communicators that dinosaurs “sugar-coat the pill of knowledge” but I’ve often wondered about the exact role these animals play in helping scientists communicate their subject. Perhaps they’re viewed by the public as little more than monsters, no more educational than dragons or the abominable snowman.

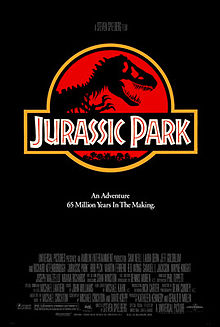

The well known science populariser and palaeontologist Stephen Jay Gould wrote an article about the nature of ‘Dinomania’ for the New York Review of Books around the time of the release of the film version of Jurassic Park. His article is wide ranging, exploring how dinosaurs have become so popular and asking if the excitement surrounding them at that time was just a fad; the result of cynical commercialisation. The most pertinent point he raises is the effect that such commercialisation has had on science communication efforts, “ In the past decade, nearly every major or minor natural history museum has succumbed (not always unwisely) to two great commercial temptations: to sell many scientifically worthless, and often frivolous, or even degrading, dinosaur products in their gift shops; and to mount, at high and separate admissions charges, special exhibits of colorful robotic dinosaurs that move and growl but (so far as I have ever been able to judge) teach nothing of scientific value about these animals.” He concedes that such animatronics would be useful if they were integrated with other educational exhibits but bemoans the fact that they are often separated from the rest of the exhibit entirely.

A further point he raises is that of the antagonistic relationship that has resulted from ‘dinomania’. He explains how, “Dinomania dramatizes a conflict between institutions with disparate purposes—museums and theme parks. Museums exist to display authentic objects of nature and culture—yes, they must teach; and yes, they may certainly include all manner of computer graphics and other virtual displays to aid in this worthy effort; but they must remain wed to authenticity”.

But if we look at the history of dinosaurs they ‘escaped’ into the public sphere almost as soon as they were discovered. They were never contained solely within the purview of science and scientists. The Victorian anatomist Richard Owen who gave dinosaurs their name collaborated with the artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins in creating the first models of these animals. The Great Exhibition of London at Crystal Palace in 1854 displayed these sculptures to the public who were astounded. Pictures, posters and replicas of the sculptures were made available to the public. Certainly, commercialisation was no recent addition.

And 22 years after the release of Jurassic Park dinosaurs are still as prominent as ever, so it seems ‘dinomania’ was no flash in the pan. My own view is that these animals are an excellent means of showing the wonder of science and nature to people, often acting as a gateway to science especially among children. Yes they may be cynically marketed and there are many inaccurate representations of dinosaurs but undoubtedly even these have evolved. The Tyrannosaurus of Jurassic Park is a much more accurate representation of the animal than the version who fought King Kong 60 years earlier. It appears that dinosaurs are well-placed to both educate and entertain with neither component mutually exclusive. The final words go to palaeontologist Bob Bakker:

“Interest in dinosaurs is not a fad. Dinosaurs are nature’s special effects, extraordinary monsters that were created not by a Hollywood computer-animation shop but by the natural forces of evolution.”

Author: Adam Kane, kanead[at]tcd.ie, @P1zPalu

Photo credit: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jurassic_Park_%28film%29#/media/File:Jurassic_Park_poster.jpg