Esteemed and valued colleague, educator and mentor to so many, Professor John Rochford, retired in September 2019 after 34 years of service. His retirement was very fittingly marked on January 10th by a symposium which celebrated the influence of John’s teaching and mentorship and the far-reaching impact he has had on his research area of wildlife biology. The symposium was organized by Prof. Celia Holland and Fiona Moloney who put together a fantastic variety of contributions. The speakers were all John’s former students who have gone on to make their mark in academia, journalism, public education and as professional ecologists and wildlife rangers.

Continue reading “Celebrating 35 years of Professor John Rochford”Pedagogy in Portugal

The sun rose over the Algarve as I stood outside on my hotel balcony, watching it. In January, imagine that! It was a beautiful start to the day and I was ready to dive into work (after a hearty Portuguese breakfast of course). I was in Portugal for a few days for a workshop on field pedagogy. For the uninitiated, that means teaching techniques and the theory behind teaching, but specifically in a fieldwork context.

I have relatively limited experience of fieldwork. I went on a few wonderful field courses at school, college, and then university, but I haven’t really done much teaching of fieldwork. I did help undergraduate students to sample river invertebrates in the river Dodder which we later identified to learn about the process of measuring biodiversity and also of using the invertebrate community to understand water quality. Other than that, I’ve little fieldwork teaching under my belt, so I was ready to learn how things are done.

Continue reading “Pedagogy in Portugal”Fieldwork, and why students need it

I recently took part in the 3rd year Terrestrial Ecology field course in Glendalough. Though I already had some experience teaching both lab work and fieldwork, this was my first time being “staff” on a trip I had previously been on as a student. It was a wonderful experience. This field course is a venerable institution of the Zoology Department: it has taken place Glendalough every year since 2007, having previously been held in the Burren and Killarney National Park. It has always been beloved by students, as seen in this video made in 2016.

Zoology students in Trinity have the chance to take part in three field courses: Terrestrial Ecology in Glendalough, Marine Biology on the rich shores of Strangford Lough, and Tropical Ecology around the ancient Rift Valley Lakes of Kenya. Here, from enthusiastic and experienced teachers, they learn skills that will stand to them in any ecological undertaking. On the Glendalough field course, students of both Zoology and Environmental Science are introduced to the techniques used to sample and survey wild animals, including Longworth trapping for small mammals, malaise trapping for flying insects, kick-sampling for aquatic invertebrates, and mist netting for birds. This last one was what brought me on the course.

Continue reading “Fieldwork, and why students need it”Donuts with a Doctor – musings on mentoring

Who doesn’t like donuts? Sugary and crispy on the outside, doughy and satisfying on the inside. And it turns out that eating a donut provides the perfect opportunity for some academic mentoring. The recent Ecology and Evolution Ireland conference put on a “Donuts with a Doctor” mentoring session that brought donut lovers together to exchange experiences on career opportunities, work-life balance, skills, mobility, and whatever else could be said between bites. Continue reading “Donuts with a Doctor – musings on mentoring”

The Evolution and Laboratory of the Technician.

First in a series of posts on life after an undergraduate degree, Alison Boyce gives an account of the life of a scientific technician.

Science, engineering, and computing departments in universities employ technicians. Anyone working or studying in these areas will have dealt with a technician at some point but most will be unaware of a technician’s route into the position and their full role in education and research.

Technical posts are varied e.g. laboratory, workshop, computer. Funding for technical support is afforded by the Higher Education Authority (HEA) to provide assistance in undergraduate teaching. This is the primary role of technical officers (TOs) after which the Head of Discipline or Chief Technical Officer (CTO) decide further duties.

History

Until the early 1990s individuals joined the university as trainee technicians. Many came through the ranks starting as laboratory attendants, a position which still exists. Trainee technicians would spend one day a week over four years working towards a City and Guilds’ qualification. At this time the occupation was mostly hands on with little theoretical work. Many started young by today’s standards (starting at 14 years old was not uncommon), and they continued to study well past diploma level. Changing the nature of the role so much that nowadays almost all technical officers have primary degrees and come with a more academic view of the position.

In 2008, it was agreed that incoming technical officers must hold at least a primary degree in order to work at Trinity College Dublin. Those looking for promotion to Senior TO would require a Master’s and to CTO, a PhD. Those already in the system would not be penalised, local knowledge and experience are recognised equivalents and rightly so. This agreement gave rise to the job title changing from technician to technical officer reflecting the removal of the apprenticeship system. Many still use the old name but it doesn’t cause offence. These qualifications represent minimum requirements. TOs constantly train, learning new technologies and procedures. It is difficult to resist the temptation of further study when you work in an educational environment.

From graduate to TO

Gaining experience in medical, industrial, or other educational laboratories is most important. Further study in areas general to laboratory work are also advantageous e.g. first aid, web design, or statistics. Sometimes researchers move into a technical role temporarily and find they enjoy it so stay on. Applying to a discipline with some relationship to your qualifications makes sense; a physicist may not enjoy working in a biological lab. Having come though the university system many graduates would be familiar with teaching laboratories and their departments. Seeing a place for yourself in the future of a discipline is vital for career progression as it is seldom you will see a TO moving from one department to another. It should be possible to adapt the role to your skills or study to meet those required for promotion.

Day to day

All labs/disciplines differ but certain core responsibilities fall to the technical staff at some point. Running practicals is the biggest responsibility during term time with design and development out of term. Some departments in science and engineering have lab and field based classes. Various modules require field sampling in preparation for the practical. Getting out on the road can be very satisfying even if you are at the mercy of nature!

If you consider what it takes to run a home you’ll have an idea of what a TO does to maintain a lab/department. Ordering supplies and equipment. When something breaks, repair it or have it mended in a cost effective way. Logging, maintaining and installing equipment, health and safety information and implementation, chemical stock control, running outreach programmes, planning and managing building refurbishment, organising social events, updating the discipline’s web pages, assisting undergraduate student projects and much more.

These are just the basic duties and do not describe the essence of technical work at university level. Firstly it is to guide, instruct, and assist in scientific matters. An analytical and practical mind is necessary. You must have a willingness to facilitate the design and execution of projects in teaching and research. If you are eager to help and learn, it’s the perfect job for you. The information base for many materials and methods is the technical staff. Local knowledge and an ability work in consultation with other departments is often key to completing a project. Ideally, when a researcher leaves the university, their skills should pass to a TO keeping those abilities in-house. Imparting them to the next generation.

If you’re very lucky, you’ll be in a discipline that encourages you to take part in research and further study. It’s wise to check where a discipline or school stands before considering work in that area. Career opportunities open up in such disciplines. CTO Specialist is a promotion given to someone with expertise of a specialist nature e.g. IT, histology. Experimental Officer is a post created to further research in a discipline and often requires some teaching.

Overall, the position is what you make of it. If you strive to improve and adapt, you’ll find it immensely rewarding. Many practical classes repeat annually but on a daily basis you could be doing anything, anywhere. Being a technical officer is stimulating and constantly changing, keeping your brain and body active. You won’t be sitting for too long when you’re surrounded by young adults in need of advice and equipment. The relationship is symbiotic, your knowledge and their enthusiasm eventually gets any problem sorted.

Author: Alison Boyce, a.boyce[at]tcd[dot]ie

Alison Boyce has worked as a technical officer at Trinity College Dublin for over 20 years. In that time, she has acted as a master-puppeteer in seeing countless undergraduate projects through to completion. Her in-depth knowledge of technical, theoretical, and practical aspects of natural sciences has made her one of the most influential figures in the history of this department.

The editorial team thanks her for taking the time to write this piece.

What do professors do?

Whenever I go home I repeatedly deal with the age old question non-academics ask academics: what do you actually do? I always find this a tricky question no matter who asks. Some people have tried to make it easier by asking me to describe a typical day or week, but this doesn’t really help as it changes a lot from week to week! In 2014 I attended five conferences and two workshops, did two weeks of fieldwork in (cold and wet!) Madagascar, and gave four seminars at different universities. I also worked on at least ten completely different research projects with different groups of people. Most weeks I’d work on one of those at least a little. But other than the research, I don’t really have an “average” week. Most weeks I’ll attend NERD club, and a meeting (or five) and I usually interact with my PhD students to some degree. But the exact details depend on the time of year (exam season/term term/outside term time), and where I am with projects, grant deadlines etc. So instead of specifically telling you what *I* do, I’ve compiled a list of the kinds of activities professors/lecturers are involved in.

Professor/lecturer jobs are often split into three areas: research, teaching and admin. However, I prefer to think of it in the same terms as on our promotion forms: research, teaching, service to your institution and service to the community. Admin sadly forms part of all of these things, like a layer of really horrible jam sticking together the cake of academia. All of these things also seem to involve a lot of emailing. If you defined my job by what I spend most time on, I’m probably a professional emailer…

Research includes fieldwork, lab work, analyses, coding/programming, planning future projects, managing finances, supervising PhD students and postdocs, writing press releases, reading papers/books, writing papers/books, writing blog posts about research, grant writing (this is the worst!), attending conferences, networking, writing reports, attending journal clubs etc.

Teaching includes giving lectures and tutorials, supervising labs, preparing lectures and labs, getting materials for labs, setting and grading essays, supervising projects and desk studies, giving careers advice, writing reference letters, putting teaching materials online, arranging timetables and room bookings (and dealing with the inevitable mix-ups that occur), providing extra reading, marking exams, invigilating, checking attendance, advising students who are experiencing difficulties, being a personal tutor etc.

Service to your institution includes sitting on committees, acting as Director or Dean of some administrative entity, promoting the institution via social media and/or traditional media, helping at Open Days, organising seminar series, providing graduate student training, internal examining theses, interacting with alumni, organising journal club, being a representative at meetings (e.g. Athena SWAN, departmental, Faculty etc… ad infinitum).

Service to the broader scientific community includes teaching on workshops, creating online tutorials, reviewing papers, being a journal editor, sitting on society committees, organising conferences/symposia/workshops, giving seminars at other institutions, organising outreach events, writing advice based blog posts, grant reviewing, organising cross-institution journal clubs etc.

There are probably many more, but this is what we came up with in half an hour!

As you can see it’s a pretty diverse job! Strangely we are mostly trained as PhD students and postdocs to do research, some service to the broader community and a little bit of teaching. This is worth bearing in mind when deciding whether a career as a professor/lecturer is right for you, as research is definitely only part of the job (at some times of year it’s very difficult to do any research at all!). However, many of the additional duties are really interesting and fun, and things like teaching and supervising students are really rewarding.

These are quite general things we do as professors/lecturers. But hopefully this is helpful if you’ve ever wondered why we’re always moaning about being busy! One final point – in general, professors/lecturers *do not* get the summer off work. My ex’s mother was convinced that I had the best job in the world because I only had to work from late Sept to June. If only that were true!

Author

Natalie Cooper

nhcooper123

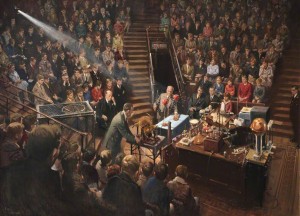

Photo credit

Cuneo estate / Bridgeman Images

The Royal Institution

Demonstrating: getting the most out of undergraduate teaching

One of the benefits of doing research in an academic institution is the opportunity to interact with undergraduate students. Students benefit from being taught by leading researchers while staff have the opportunity to inspire the next generation of scientists. Practical lab classes are usually a focal point of this direct interaction between student and researcher. However, due to the logistics and practicalities of managing large class sizes, PhD students are playing an increasingly important role as teaching assistants or lab demonstrators. In one of our recent NERD club sessions, Jane Stout led an interesting discussion about the importance of practical classes, the role of postgraduate students and best practice for what makes a good demonstrator. Here’s a compilation of our thoughts.

One of the benefits of doing research in an academic institution is the opportunity to interact with undergraduate students. Students benefit from being taught by leading researchers while staff have the opportunity to inspire the next generation of scientists. Practical lab classes are usually a focal point of this direct interaction between student and researcher. However, due to the logistics and practicalities of managing large class sizes, PhD students are playing an increasingly important role as teaching assistants or lab demonstrators. In one of our recent NERD club sessions, Jane Stout led an interesting discussion about the importance of practical classes, the role of postgraduate students and best practice for what makes a good demonstrator. Here’s a compilation of our thoughts.

Why do we teach undergraduate practical classes?

Lab practicals can be expensive, time consuming and difficult to manage so why bother including them in the undergraduate curriculum? We think that the main reasons are to engage students in the subject and to teach them how to become scientists. Every student has a different learning style and practical classes can help to address this issue. For many people, sitting in a large lecture theatre can be a rather passive and ineffective learning experience. Practical classes offer an opportunity for active learning and hands on experience. Students can deepen their understanding of a topic and go beyond lecture content to form their own questions. They also learn the skills and techniques necessary for future employment, whether that is in a research environment or not. From the lecturer’s point of view, practical classes are useful opportunities to interact with students and to assess their level of understanding.

Why demonstrate? What are the benefits for a postgraduate student?

Large practical classes would not be possible without a team of demonstrators, so lecturers rely on their help. But there are also many benefits for postgraduate students. Demonstrating is excellent teaching experience and a good way to improve your own understanding of a subject. Demonstrators learn how to explain concepts to non-specialists and how to handle large groups of people; essential skills for any career. Challenging and unexpected questions from students also teach you to think on your feet (I’m a zoologist but at various stages I have feigned expertise in biochemistry, plant sciences and microbiology). It’s all too easy for postgraduates to get stuck in a very narrow focus of their particular research area but demonstrating is a great way to broaden and develop your skills. Furthermore, if you’re stuck on a particular research problem, demonstrating can be a fun and rewarding moral boost: you may be stuck in your project but at least you know enough to help somebody else! Overall, demonstrating is fun, rewarding and a good skills/CV boost. The pay isn’t bad either…

Why do we need postgraduate demonstrators? What are the benefits for undergraduate students?

Demonstrators bridge the gap between undergraduates and lecturers. Postgrads are less intimidating than lecturers and direct interactions with demonstrators can help students to feel more involved in a class. Interacting with demonstrators also gives undergrads an insight into what it’s like to work in research and academia. Chatting to your demonstrator helps to put a human face on science and to break down the mystiques of academia. We all agreed that it’s important to remind undergraduates that demonstrators (and lecturers) are not just teachers: they are the ones doing the research that ends up in the text books.

What makes a good demonstrator?

We’ve all had good (and not so good) demonstrators so what are the characteristics that one should try to develop? The two most important things are preparation and enthusiasm. Demonstrating is a professional commitment so it should be treated as such. Make sure to read the manual beforehand, understand what you are teaching and be prepared for students’ questions. The best way to keep a class engaged and interested is to show some of those qualities yourself. Be approachable, friendly and willing to help. It’s important to be confident in your explanations and behaviour but also don’t be afraid to say “I don’t know” swiftly followed by “but I can find out” or “this is how you can find out”. Try to explain concepts without too much jargon but don’t patronise by over-simplifying.

Combining all of the advice and pointers from above, here’s our best practice guide on how to be a good demonstrator.

- Be cheerful and positive, not grumpy and negative: there’s always something that can be taken from any practical session no matter how boring it may appear.

- Encourage students to work as a group and to help each other.

- Ask questions and be proactive: don’t just wait for students to come to you with their problems, engage them in discussions instead.

- Try to pre-empt common problems and mistakes but don’t just give students the answer: explain things in a clear and logical way and talk students through the steps they need to get to an answer.

- Be fair: give an equal amount of attention and help to all students on your bench, not just the ones who ask the most questions.

- Be patient and empathetic. You may get frustrated explaining the same concept for the umpteenth time but try to remember what it was like when you were a novice yourself. Pass on any tips or skills that helped you to learn a particularly tricky concept.

- Interact with other demonstrators and provide constructive feedback to lecturers.

- Be inspirational! Remember that you are an ambassador for your subject and undergrads will look to you to see what life is like as a researcher. You should be an enthusiastic and positive representative for your subject and inspire the researchers of tomorrow!

Author: Sive Finlay, @SiveFinlay

Photo credit: http://www.w5coaching.com/meet-john-nieuwenburg/

Dying without wings: Part II

Last week our newest EcoEvo@TCD paper came out in PRSB (it will be Open Access soon but currently it’s behind a pay wall – feel free to email me for a copy in the meantime. Code for the multiple PGLS models can be found here). This paper is exciting for me for two reasons – firstly because the science is really cool and secondly because of how it came about. In a previous post I explained the results of the paper. Today I want to focus on how it came about. Continue reading “Dying without wings: Part II”

Blog-tastic!

Andrew Jackson and I started a new module this year called “Research Comprehension”. The aim of the module is simple: to help students to develop the ability to understand and interpret research from a broad range of scientific areas, and then to develop opinions about this research and how it fits into the “big picture”. In our opinion, this is perhaps the most important thing an undergraduate can get out of their degree, because no matter what you do when you graduate, in most jobs you will be expected to read, understand and interpret data. Often this will be in a subject you are unfamiliar with, or use unfamiliar methods or study organisms. So being able to understand this information is key!

The module revolves around the Evolutionary Biology and Ecology seminar series in the School of Natural Sciences, so the topics are broad and cover whole organism biology, molecular biology, genetics, plants, and animals etc. Students attend the seminar on a Friday and read some papers sent on by the speaker. There is then a tutorial on a Monday with a member of staff who has interests in the area of the seminar. This gives everyone a chance to clear up any confusion and to discuss what they liked (and disliked) about the seminar. The continuous assessment for the module is in the form of the blog posts we will post here. Thus the module also aims to improve the students’ abilities to communicate all kinds of scientific research to a general audience, a skill that is currently in great demand.

From next Wednesday onwards we will select a few blog posts to put onto EcoEvo@TCD. These may not necessarily be the posts that get the best grades, but they’ve been chosen to reflect the diversity of angles the students have taken to communicate the parts of the seminar they found most interested. Overall we’ve been extremely impressed with the quality of their blog posts, so we hope you enjoy reading them!

Author: Natalie Cooper, ncooper[at]tcd.ie, @nhcooper123

Image Source: Jorge Cham, www.phdcomics.com

Dear students (part 2)

Part 2 of our lecturers’ letter of advice to their students …

Dear students,

We really enjoy teaching you but there are some things we wish you knew…

6. We don’t want you to fail your exams

Every year people come out of the exams complaining (or sometimes weeping!) about how they’ve definitely failed and the lecturer was clearly being mean on purpose so everyone would fail. This upsets us because it shows that you don’t trust us to be decent human beings and/or professional educators. Generally speaking, everyone does fine on the exams we set. If, for some reason (and its rare) everyone does obviously badly on an exam then it may be the case that something was misunderstood or an inappropriate question was set. When this happens we usually re-mark the exam or change the marking scheme appropriately to make it fair, and so that the number of people who pass is in line with the other exams.

7. Getting 59% overall for the year doesn’t mean you were 1 mark away from a 2.i

Your final year mark is made up of all the coursework you’ve done, plus your exams, and comes out of a total of about 1000 marks. So 1% is not equal to 1 mark. For example, if 50% of your course was continuous assessment and you got 60%, you still need 60% in your exams to get 60% overall. Often a single percent overall means finding 10% more from an exam, the equivalent of changing your grade for an essay from a 2.i to a 1st. Sometimes it is possible to find an extra mark or two but 10% suggests that the person marking the exam made a serious error, which is very unlikely. At Trinity College Dublin everything in the final year is marked, then checked by at least two other people, one of which is an external examiner who keeps standards level with those across Europe. The project is independently marked by at least two people, as well as being checked by the examiner.

8. Collective success might be more akin to collective mediocrity

Studying as part of a group can be a fun way to revise for exams, and provide a challenging environment where you can bounce ideas off each other and learn. However, there is a potential downside. Exam study groups can often produce generic essays that have been carefully prepared by the collective. In the worst case scenario, this can drag everyone towards the mean. Furthermore, unoriginal and repetitive answers can bore the pants out of the person marking them.

9. Question spotting is a terrible idea

People have somehow got the idea that they can get away with only studying one or two topics before an exam because the same topics come up year after year. Whilst this is true, precisely the same questions do NOT appear each year, and at some point we may stop using any given topic. This question-spotting leads to people learning the “answer” to a previous year’s question and trying to apply it to the paper in front of them. Not answering the question before you in the exam, but instead regurgitating and shoe-horning in a prepared answer will not gain you marks. By all means be strategic in your revision but make sure you cover the whole course, but even more importantly, make sure you answer the questions you are given. Never rely on topics remaining the same from year to year – course content changes, as do lecturers, so you may find yourself in a situation where none of your topics come up if you only revise some of them. If that happens it’s no-one’s fault but your own!

10. Education is a privilege. Enjoy it!

Believe it or not, we hate exams as much as you do! However, we need to assess students somehow; we can’t just give everyone a degree. If we did, what would be the point in studying? Because of this, exams remain part of being a student. Notice that we say “a part” of being a student. As a student you should be here to learn as much as you possibly can from some of the leading academics in your subject. You should not be trying to learn as little as possible so you can pass an exam. Yet the question we get asked the most is “what do I need to know for the exam?”. This is infuriating because it implies that only knowledge needed to pass the exam is valuable, when learning for the sake of learning is one of the most wonderful experiences in life. In addition, many of the things you’ll learn as a student, like presentation skills, teamwork, communication skills, time management etc. are not worth any marks in exams. But these are the skills employers are looking for. Don’t waste the opportunity to improve your career prospects and general knowledge of science just because it doesn’t count towards your final grade. Education is about so much more than that.

Yours sincerely,

Natalie Cooper & Andrew Jackson (Assistant Professors at TCD)

@nhcooper123 @yodacomplex

ncooper[at]tcd.ie, a.jackson[at]tcd.ie

Image source:

readingforall101.blogspot.ie