“The research reported here involved lethal sampling of minke whales, which was based on a permit issued by the Japanese Government in terms of Article VIII of the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling. Reasons for the scientific need for this sampling have been stated both by the Japanese Government and by the authors.”

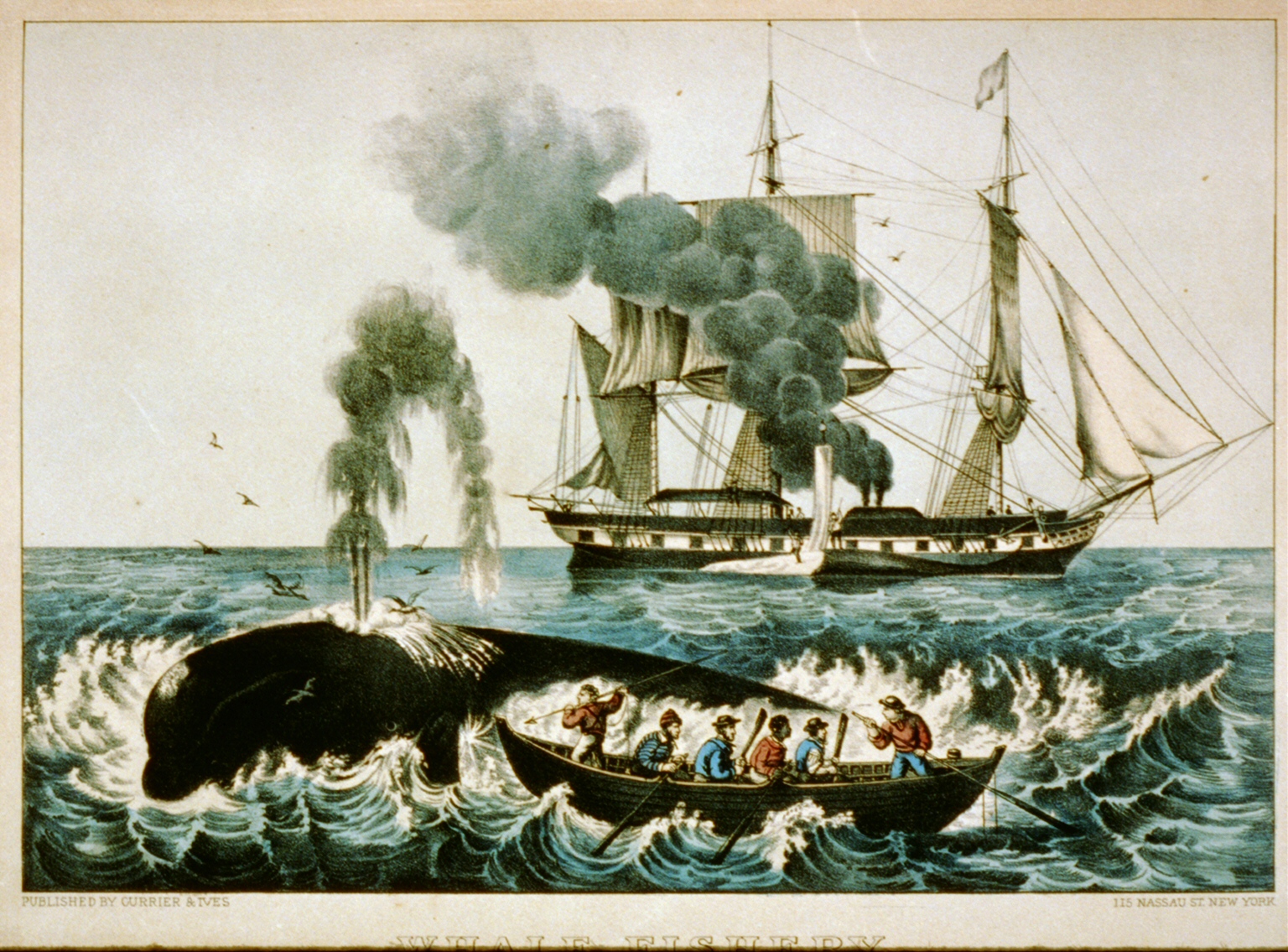

With these words I realised I’d stumbled on that semi-mythical creature, a paper that was the result of scientific whaling. Scientific whaling, if you don’t know, is how the Japanese government justifies hunting whales. Whales have been hunted since time immemorial but due to advances in technology by the mid 20th Century stocks were overexploited to such an extent that many species were pushed to commercial extinction (and possibly, such as in the case of the North Pacific right whale, actual extinction). In 1986 the unprecedented action was taken to ban commercial whaling globally to allow populations to recover. Since then small numbers of whales have continued to be caught, almost exclusively by counties with strong historical ties to whaling such as Norway, Iceland and Japan.

Whales can be caught either commercially or for science. Norway and Iceland whale commercially, selling whale products both locally and internationally through a carefully controlled trade. Japan catches whales for scientific purposes and then sells the meat in accordance with the rules of Article VIII of the Convention. According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan,

“The research employs both lethal and non-lethal research methods and is carefully designed by scientists to study the whale populations and ecological roles of the species. We limit the sample to the lowest possible number, which will still allow the research to derive meaningful scientific results.”

The paper that caught my interest is titled “Decrease in stomach contents in the Antarctic minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) in the Southern Ocean”. There are several ethical questions that the paper raises:

1) Can the samples be obtained without killing the whales?

2) Was the sample limited to “the lowest possible number” that allowed “meaningful scientific results” to be obtained?

3) Was the science worth it?

The first question is arguably the easiest to answer. Investigations of stomach contents commonly requires killing the animal whose stomach contents are desired. While non-lethal methods are available, they are difficult, time-consuming and are most effective on small animals in a captive environment. Thus the killing of whales to examine their stomach contents is not unreasonable.

The second question is harder to answer. Over the course of the 20-year study period, 8,468 whales were killed by the Japanese, an average of 423 minke whales per year. Of those, 5,449 had stomachs containing food, or 279 per year. This sample size is definitely sufficient to give statistically significant results but is it ‘overkill’ (to use the obvious pun)? Looking through my collection of papers on diet analysis, it definitely appears so. A brief survey showed that sample numbers generally range in the low tens (10-50) of specimens. Numbers only went up when sampling commercial species (such as squid or fish) or when opportunities arose. If smaller numbers are accepted by the research community, questions must be asked as to why such high sample numbers were deemed necessary. Of course, if the whales were sampled for other studies and this study was simply an attempt to use the data in as many ways as possible then my concerns are baseless.

The final question is also the most contentious. Who is to say whether the science is worth it or not? The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan said that its research:

“. . . is carefully designed by scientists to study the whale populations and ecological roles of the species. . . The research plan and its results are annually reviewed by the IWC Scientific Committee.”

If it has been assessed by the Japanese government and the IWC (International Whaling Commission) as being necessary, who are we to argue? We need to carefully look at the research being done. On the basis of this paper, I am not convinced. The study uses stomach content analysis to determine that krill availability (the food source of minke whales) has decreased over the last 20 years. Two hypotheses are put forward to explain this decrease: krill populations are being affected by climate change or there is increased interspecific competition for krill as other species increase in population size due to reduced hunting pressure. They conclude:

“Thus, continuous monitoring of food availability as indicated by stomach contents and of energy storage in the form of blubber thickness can contribute important information for the management and conservation under the mandates of both the IWC and CCAMLR of the krill fishery and of the predators that depend on krill for food in the Southern Ocean”

I disagree. They are using stomach contents as a proxy for assessing krill populations, yet it would be far easier and less ethically challenging (something I will return to in my next post) to simply sample the krill. I can see little reason why lethal sampling is required to collect this data, though I’m happy to be persuaded otherwise.

Having not been convinced by this study, I was still willing to believe that scientific whaling was producing good, robust, scientific data that could not be obtained through non-lethal methods. In my search for confirmation or rejection of this hypothesis I came across this report entitled “Scientific contribution from JARPA/JARPA II”. It lists publications that have resulted from Japan’s scientific whaling for the period 1996-2008. In that time, 101 peer-reviewed articles were published and 14,643 whales were killed, 88% of which were minke and 79% of those caught were caught in the Antarctic. Yet despite this seeming wealth of data, the IUCN still considers the Antarctic minke whale to be Data Deficient. Given that most of the papers that have been produced as a result of scientific whaling are related to stock assessment, the lack of an accepted stock level is rather telling in its absence. The rest of the papers seemed to be related to genetic studies, which are possible to do without lethal sampling.

This is, admittedly, a very preliminary survey of the literature resulting from scientific whaling. It can also be claimed that as an ecologist I’m against whaling regardless of the scientific or economic merits. This is not the case. As a disclaimer, I have eaten whale meat while in Norway. It is a sustainable fishery which is carefully monitored. In fact, if I was to feel morally dubious about anything from that meal it would have been my main course of halibut, which has been systematically overfished.

This raises other ethical questions which I hope to address in my next post. However, for now, a conclusion is due. And in my mind it is this: the science that is being produced through scientific whaling does not justify the number of whales being caught. Most of the science can be done through other sampling methods and that which cannot has not been shown to be necessary. Given the costs, the controversy and the decreased ability to sell the meat the case for scientific whaling rests on the quality of the science and ultimately that science is lacking.

Author: Sarah Hearne, hearnes[at]tcd.ie, @SarahVHearne

Image sources: Wiki Commons and Sarah Hearne